The purpose of this article is to share observations made after performing 90 consecutive micrograft and minigraft megasessions for the treatment of male pattern baldness. Micrograft means grafts with I or 2 hairs, mini grafts are those with 3 or 4 hairs, and a megasession is a procedure in which more than 1000 micrografts and mini grafts are inserted in a single session. Between March of 1994 and June of 1996, the author performed 90 consecutive micrograft and minigraft, megasessions on 86 men and 4 women ranging from 21 to 67 years of age (average age, 42 years). The surgical team consisted of three surgical assistants and a plastic surgeon. Today, usually between 1500 and 2000 grafts per session are performed in about 4 to 6 hours, with up to 2495 grafts done in a single session. All procedures were done under intravenous sedation and local anesthesia. A donor horizontal ellipse of scalp is harvested from the occipital area; the grafts are made out of it and then inserted through small slits. The procedure has been found to he safe, and predictable with natural and aesthetically pleasing results, and there were no serious complications. The Only complication found in this group was self-resolving Inclusion cysts (ingrown hairs) occurring in 9 of 90 patients (10 percent). Even through the hair density achieved in a single megasession is limited, there is a high level of patient satisfaction: 83 of 85 patients were satisfied (97.65 percent). (Plast. Resonstr. Surg. 100:1524, 1997.)

For many years, multiple procedures have been available for the treatment of male pattern baldness. These include punch grafts,1-2 strip grafts,3 scalp flaps, 4-6 scalp reductions, 7-10 tissue expansion, 11-13 combination of tissue expansion and flap advancement,14 transposition,14 and, more recently, the use of scalp extenders.15 For the most part, these techniques tend to require too many sessions. The punch graft technique, as well as the temporoparieto-occipital flaps and the scalp reductions, typically takes four surgical procedures, leaving noticeable scarring and a result that looks unnatural.

The tissue expansion and combination of expansion and flaps typically take two sessions and often require additional touch ups. Also, there is the inconvenience of significant deformity during the 2 to 3 months of expansion, and patients often end up with a visible scar at the front hairline.

The use of single hair grafts was initially reported by Tamura in 1943 for reconstruction of pubic hair16 and in 1953 for reconstruction of eyebrows.17 In 1980, single hair grafts as eyelashes were reported by Marritt.18 Nordstrom 19 and Marritt 20 introduced in 1981 and 1984, respectively, the use of single hair grafts (micrografts) to improve the frontal hair line after hair transplantation as an attempt to provide a natural appearance. Subsequently, Uebel 21,22 introduced the concept of micrografts (I to 2 hairs/graft) and minigrafts (3 to 4 hairs/graft) in large numbers to cover the entire affected area while obtaining excellent results without visible scars.

Inspired by the work of Uebel, I started performing micrograft and minigraft megasessions in 1994, making a special effort within the bounds of reason and safety to gradually increase the number of grafts per session and trying to accomplish the best possible results in one session. This report includes my personal experience with 90 consecutive micrograft and minigraft megasessions.

Methods

Between March of 1994 and June of 1996, 1 performed 90 consecutive micrograft and minigraft megasessions. All patients were carefully selected with good supplies of donor hair and realistic expectations. Postoperatively, they were followed closely to evaluate potential complications such as infection, hematoma. dehiscence of donor site, deforming scars, inclusion cysts or ingrown hairs, and absent hair growth.

The majority of the patients were Caucasians; however, there were some Hispanic, Mediterranean, Indian, Pakistan, Oriental, and black American patients. For evaluation of patient satisfaction, only 85 patients were considered, because two were lost to follow-up and three were less than 6 months postoperative. The 85 patients were personally interviewed by my office staff regarding their level of satisfaction.

Technique

All procedures were performed in an office surgical suite setting under intravenous sedation with the use of Versed (Midazolam), Sublimaze, and local anesthesia. Vital signs, oxygen, and electrocardiogram readings were monitored throughout the procedures.

The sedation was used in most cases only to administer painlessly the local anesthetic; then, the patient was allowed to be awake for the majority of the surgical time. A total of 30 to 40 ml of 0.5% Marcaine (Bupivacaine) with epinephrine (1:200,000) was used to block the occipital and supraorbital nerves and to provide ample subcutaneous infiltration to the donor site and the upper forehead. This allowed for total numbness for the duration of the procedure.

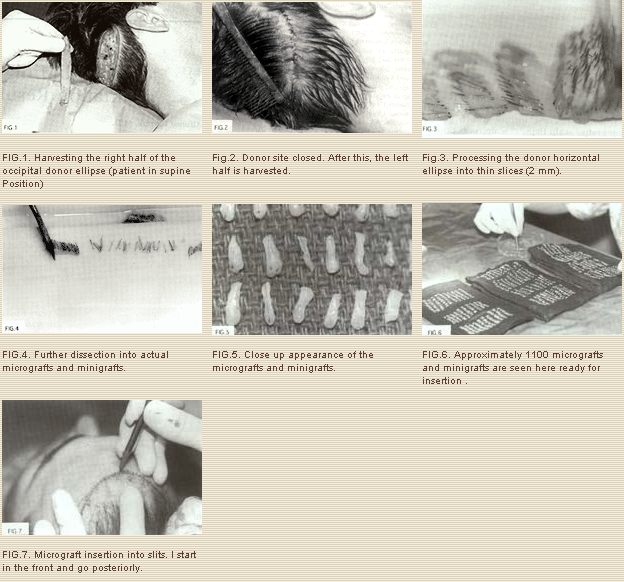

In addition, a total of approximately 160 ml of 0.25% Xilocaine with epinephrine (1: 200,000) was used throughout each case for tumescent infiltration. Our four-person surgical team consisted of two cutting grafts and one assisting the author in inserting the grafts. (I personally inserted every graft.) With the patient in the supine position, a horizontal occipital ellipse 15 to 25 cm long by 1.5 to 2.5 cm wide was harvested; the size depended on the number of grafts to be made and the density of the donor site. The patient’s head was turned to the left, allowing for a comfortable harvest of the right half of the ellipse, which was immediately handed to my assistants for cutting it into micrografts and minigrafts (Figs. I through 6).

We used Personna prep blades to make the initial dissection of the donor scalp ellipse, creating thin slices (2 mm). These thin slices are then turned sideways to further dissect into the actual grafts with 22 Personna blades. At this point, the tumescent solution was infiltrated to the front one-third of the area to be treated (20 to 30 ml). As soon as blanching occurred, we started inserting grafts. We have found it useful to do the tumescence segmentally in thirds to have the maximum benefit of the epinephrine in this long procedure. Additional solution was infiltrated as needed.

About 400 micrografts were inserted in the front 0.75 to 1 inch of the new hairline by making small slits with a 22.5 Sharpoint blade or a 65 Beaver miniblade and immediately inserting a micrograft with a smooth jeweler’s forceps (Fig. 7). Posterior to this, we continued with either a 65 Beaver or a Feather 11 Personna blade for the insertion of the remaining minigrafts.

As the fibrinogen turns into fibrin, the grafts adhered to the recipient area, allowing us to insert additional grafts between the ones inserted earlier. This minimizes graft pop-out. Repeating this periodically throughout the case makes it possible to accomplish dense packing of the grafts, especially in the front where the best coverage is needed. The closest we have been able to insert grafts is about 1 to 1.5 mm from each other.

For dressing, we used adaptic as a first layer, followed by a wet kerlix in normal saline, a dry kerlix, and finally one or two 3inch Ace bandages. A gram of Ancef was given intravenously on induction of the sedation, and after surgery we prescribed 500 mg of Keflex by mouth, 4 times a day, for 3 days and Vicodin I-II, by month, every 3 to 4 hours as required for pain for a few days. The patient was seen at 48 hours to remove the bandages and was allowed to gently shampoo his hair daily from then on. At 7 to 10 days the occipital sutures are removed.

Results

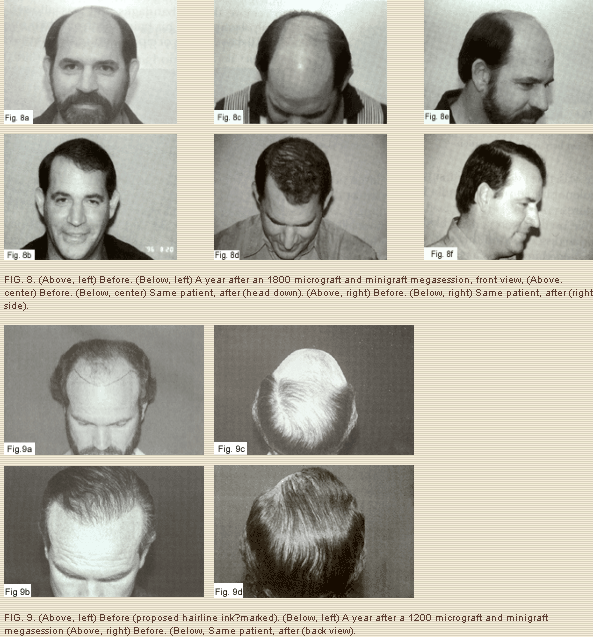

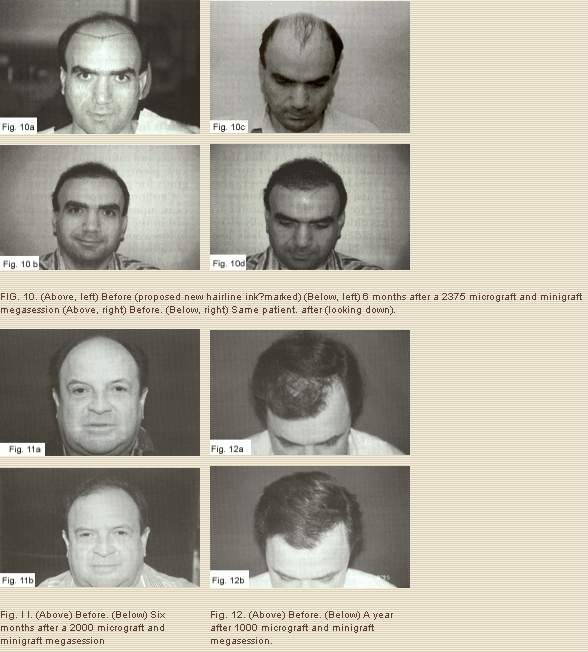

The transplanted hair started growing immediately; however, at about 10 to 30 days, in most patients a variable amount of transplanted hair went into a telogen phase (it fell off), after which it regrew in 3 to 4 months. Such growth became thicker and healthier by 6 to 8 months, and it took about a year for the final result. We estimate that approximately 90 to 95 percent of each individual graft ends tip growing healthy hair (Figs. 8 through 12).

Self-resolving ingrown hairs (minor inclusion cysts) was the only complication found in our series. It occurred in the first 2 to 4 months in 9 of 90 patients (10 percent), but we have been able to reduce that occurrence to almost zero by placing the grafts more superficially. No patient developed infection, hematoma, dehiscence of the donor site, deforming scars, or any other complication, and all had hair growth. Of the 85 patients personally interviewed by my office staff, we were happy to learn that 81 of 85 (95.29 percent) were very satisfied and 2 of 85 (2.35 percent) were satisfied for a total satisfaction rate of 97.65 percent. Only 2 of 85 (2.35 percent) were dissatisfied; they had hair growth but complained it was too thin. They were interested, though, in trying it again, which may be interpreted as not total dissatisfaction.

On the basis of this study, we know that the results are safe and predictable for up to 2495 micrografts and minigrafts (approximately 6000 hairs) in a single session. This procedure required a donor ellipse of good density that measured 24 cm long X 2.5 cut wide at the widest area. This is probably the upper limit of what one can harvest without donor site morbidity. Furthermore, an extensive area of baldness must exist to accommodate this many grafts. The procedure took us 7 hours, including a lunch break for us and the patient.

As mentioned earlier, for many years I have followed the surgical options in hair transplantation. I feel that we have the obligation to help our patients choose the procedure that best fits their needs. Naturally, the ideal solution for male pattern baldness should be safe, give a natural result both in the short and long run, result in no visible scarring, and have minimal downtime. For the aesthetic treatment of male pattern baldness, the use of micrograft and minigraft megasessions seems to be a good option as long as the patient has good quality of donor hair and realistic expectations. We are only distributing the existing hair in a more desirable way to achieve better coverage. The patient must be aware that we cannot achieve the density he once had. It will never match the density of the temporal or occipital areas. If the patient does not have healthy hair donor areas or if there is a very limited amount, he is not a candidate for surgery.

Interestingly, the hair from the temporal and occipital areas in most cases of male pattern baldness tends to remain growing for most of the lifetime. We have learned from the use of punch grafts that when harvested from these areas, the transplanted hair generally tends to grow hair in the recipient areas for as long as it was going to do so in its site of origin. This is a very encouraging finding. Careful patient selection is important. Special caution should be exercised with young patients (under 30 years of age), as it is impossible to predict how severe the baldness will become. One must always think in terms of the long run and be conservative, anticipating a mature hairline to provide better density.

The front hairline frames the upper boundary of the face, making it imperative to provide the best coverage possible at this location. It is wise to leave some degree of donor site in reserve for potential later use. In the worst case scenario, we cover only the front. In most cases, however, we have covered the entire head.

Younger patients should be aware that their hair loss will continue and that further surgery will very likely be needed. This, however, also applies to all patients, because, unfortunately, hair loss continues for a lifetime. I prefer to operate on patients older than 30 (ideally 40 or older) because in older patients the hair loss pattern is better established, but younger patients deserve cautious consideration inasmuch as baldness can be psychologically quite devastating.

In the past before using conventional punch grafts, it was very important to consider multiple factors in patient selection, such as hair type and color as it related to skin color, to obtain an acceptable result. However, with the introduction of micrografts and minigrafts, such factors are not so important. Artistic insertion of a large number of micrografts to the front hairline, as described, allows for a natural result in virtually every case. The fact that a natural hairline can be predictably created permits us to start in the front and work our way posteriorly.

It is important to use magnifying loupes for cutting the donor piece of scalp into micrografts and minigrafts. We use 3.5 magnification and plenty of light, especially when Cutting grafts for patients with blond or gray hair. Caution is recommended in black Americans; upon cutting the grafts, we found that within the thickness of the scalp the hair shafts follow a spiral direction, increasing the degree of difficulty in preparing the grafts. This also was found to some degree in patients of Mediterranean origin. Naturally, in black Americans there is a greater risk for hypertrophic scarring and keloids. The author suggests a preliminary test under local anesthesia several months in advance by making several small incisions in the scalp in all patients on whom keloid scarring may be a concern. For reconstructive cases (i.e., oncologic resections, congenital defects, burn alopecia), scalp flaps, tissue expanders, pedicled flaps, or free tissue transfers with microvascular anastomosis certainly would be better options.

Conclusions

The micrograft and minigraft megasession has been found to be a safe procedure. Natural and aesthetically pleasing results without visible scarring were achieved in this group of patients in one session. Even though the hair density achieved in a single megasession is limited, there is a high level of patient satisfaction. The procedure may be repeated for additional density.

Alfonso Barrera, M.D.

West Houston Plastic Surgery Clinic, P.A.

915 Gessner Rd., Suite 825

Houston, Texas 77024

References

1. Orentreich, N. Autografts in alopecias and other selected dermatological conditions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 83: 463, 1959.

2. Stough, D. B., III. Punch scalp autografts for bald spots, Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 42: 450, 1968.

3. Vallis, C. P. Hair transplantation for male pattern baldness. Surg. Clin. North Am. 51: 519, 1971.

4. Juri,J. Use of parieto-occipital flaps in the surgical treatment of baldness. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 55: 456, 1975.

5. Elliott, R. A., Jr. Lateral scalp flaps for instant results in male pattern baldness. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 60: 699, 1977.

6. Mayer, T. G., and Fleming, R. W. Short flaps: their use and abuse in the treatment of male pattern baldness. Ann. Plast. Surg. 8: 296, 1982.

7. Blanchard, G., and Blanchard, B. Obliteration of alopecia by hair lifting: A new concept and technique. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 69: 639, 19717.

8. Alt, T. H. Scalp reduction as an adjunct to hair transplantation: Review of relevant literature, presentation of an improved technique. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 6: 1011, 1980.

9. Unger, M. G. The modified major scalp reduction. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 6:1011, 1980.

10. Brandy, D. A. Point: Extensive scalp-lifting., J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol.14: 1420, 1988.

11. Manders, E. K., Au, V. K., and Wong, R. K. M. Scalp expansion for male pattern baldness. Clin. Plast. Surg. 14: 469, 1987.

12. Adson, M. H., Anderson, R. D., and Argenta, L, C. Scalp expansion in the treatment of male pattern baldness. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 79: 906, 1987.

13. Anderson, R. D. Expansion-assisted treatment of male pattern baldness, Clin. Plast. Surg. 14: 477, 1987.

14. Anderson, R. D. The expanded “BAT” flap for the treatment of male pattern baldness. Ann. Plast. Surg.. 31: 385, 1993.

15. Frechet, P. Scalp extension.J Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 19: 616, 1993.

16. Tamura, H. Pubic hair transplantation. Jpn. J Dermatol. 53: 76, 1943.

17. Fujita, K. Reconstruction of eyebrows. La. Lepr, 22: 364, 1953.

18. Marritt, E. Transplantation of single hairs from the scalp as eyelashes. J Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 6: 271, 1980.

19. Nordstrom, R. E. A. “Micrografts” for improvement of the frontal hairline after hair transplantation. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 5: 97, 1981.

20. Marritt, E. Single-hair transplantation for hairline refinement: A practical solution. J Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 10: 962, 1984.

21. Uebel, C. O. A new method for pattern baldness surgery. Presented at Jornada Carioca Cirurgia Plastica, Rio dejaneiro, Brazil, August 1986.

22. Uebel, C. O. Micrografts and minigrafts: A new approach to baldness surgery. Ann. Plast. Surg. 27: 476, 1991.